Anglers from all over the state head out onto Lake Michigan in the summer in hopes of catching Chinook salmon, an introduced species that persists in the lake through a combination of natural reproduction and stocking of hatchery-raised fish. Managers would like to know the proportion of wild fish in the lake so they can adjust stocking levels to create a Chinook salmon population that can be supported by the prey base that is present. With alewife, the main prey of Chinook salmon, on the decline in Lake Michigan, making sure the population won’t overwhelm the prey base is more important than ever. In addition, stocking fish is expensive. If managers know how much of the Chinook population is wild, they will also know how to stock only as many fish as necessary to sustain the popular sport fishery for the species. The Great Lakes Fishery Trust sponsored research into Chinook salmon otolith microchemistry intended to help managers understand how much of the population is coming from hatcheries and how much is coming from natural reproduction. Researchers also wanted to know which areas were producing the most wild fish, an important first step in habitat protection and restoration.

Otolith Microchemistry Modeling

A research team led by Dr. Rick Clark, Dr. Kelly Robinson (now at University of Georgia), and Alex Maguffee at Michigan State University investigated these questions using a previously developed model of otolith microchemistry in juvenile Chinook salmon. The model used the chemical signatures of various geographical features to identify the tributary or hatchery where juvenile fish originated and was validated using known-origin juveniles and adults.

However, use of the same model to identify the origins of adult fish caught in the open waters of Lake Michigan didn’t work as well as expected. The model assigned all sampled fish from the sport fishery as having originated in tributaries of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, and even misclassified some known-origin fish from tributaries in Wisconsin to Lower Peninsula tributaries. Additionally concerning was that the errors were concentrated in certain regions, indicating model bias.

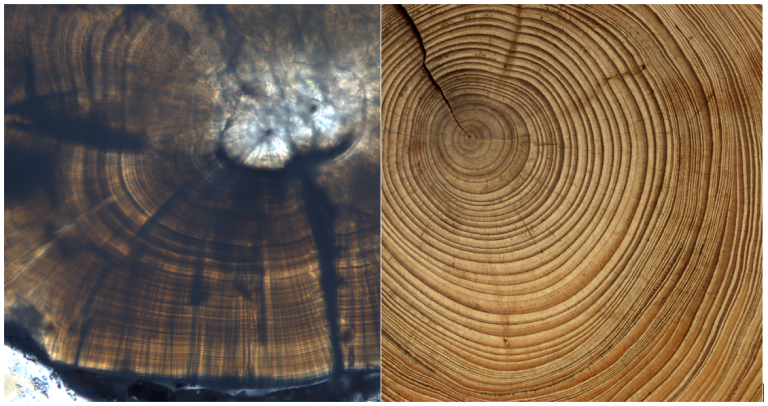

A juvenile otolith (left) next to tree rings (right). Image courtesy of yubariver.org.

What Are Otoliths?

Otoliths are bone-like structures made of calcium carbonate that are found just under the brains of bony fish. The fish’s body deposits calcium carbonate onto the otoliths as the fish grows, resulting in rings that represent different periods in the fish’s life, similar to the growth rings on trees. By analyzing the different rings, scientists can determine things like how old the fish is and how fast it has grown. Many researchers have also used chemical analysis of otoliths to study where fish hatched, what they eat, and when they migrate.

Key Findings

- Researchers were unable to identify the natal origins of adult Chinook salmon using their validated otolith microchemistry model trained on juveniles.

- This result suggests that otolith chemistry may be more complicated than previously thought; one possible explanation is that otolith composition may change or erode as Chinook salmon age, leading to adult fish with different otolith composition than they had as juveniles.

- Scientists have long thought that otolith composition is stable throughout a fish’s life, so that the inner regions of the otolith reflect the juvenile environment of an adult fish. The possibility that the inner regions change as a fish ages could have significant implications for otolith microchemistry research as a whole and in the Great Lakes.

- Much more research would be needed to show whether otolith composition changes or erodes over a fish’s life, but this research still shows the need for caution when interpreting models of fish natal origin based on otolith microchemistry.

Significant Outcomes for Lake Whitefish Research

This research concludes that otolith microchemistry cannot be used to determine the natal origins of lake whitefish because the otoliths reflect maternal, rather than incubation site, influences. Previous research has found differences in otolith microchemistry in groups of other species of Great Lakes fish incubated in different environments; however, this research suggests that those differences may not reflect environmental variation, but rather maternal influences, sounding a cautionary note for the use of otolith microchemistry studies in delineating fish populations in the Great Lakes.

Learn More

For more information, please contact the project primary investigator, Dr. Rick Clark, at [email protected].

Disclaimer

Research Notes includes the results of GLFT-funded projects that contribute to the body of scientific knowledge surrounding the Great Lakes fishery. The researcher findings and grant result summaries do not constitute an endorsement of or position by the GLFT and are provided to enhance awareness of project outcomes and supply relevant information to researchers and fishery managers. Researcher findings are often preliminary and may not have been peer-reviewed.

Related Reading

- Cracking the Code of Lake Whitefish Otoliths Complicates Stock Delineation

- Recruitment Dynamics of Lake Whitefish and Cisco in the Upper Great Lakes

- Using Genomics Techniques to Delineate Lake Michigan Whitefish Stocks

- Exploring Disease Susceptibility and Its Impact on Lake Whitefish Recruitment

- Nearly six decades of recruitment trends for Lake whitefish and Cisco in the Great Lakes